After learning about V8 exploitation, I became to be interested in the security of Chromium. After a period of thinking, I decided to start by learning about the security models of Chromium and then continued to learn how to exploit Chromium vulnerabilities. Therefore, this article is an introduction to Chromium security models which I had learned recently.

Welcome to contact me if you find some mistakes in this article!:-)

Site Isolation

Site isolation is a new security feature of Chrome. Actually, chrome has already had a multi-process architecture that distributes each tab as an individual process. However, it is still possible for a malicious website to steal significant information from another website. For example, the different frames in a single tab still run in the same process so they all can access the memory regions owing to this process. After exploiting some bugs(or Spectre) in the renderer, the malicious website may access the important information of other sites stored in memory.

Therefore, to make it safer, the development team of chrome decided to add Site Isolation to the chrome. With this feature, every site(not every tab) will have its own renderer process which means that the different frames in the same tab will have their own process and memory region.

Moreover, there are some other features that are associated with site isolation called CORB. I record it shortly so that when I forget I can review them conveniently.

CORS

Before introducing the CORB, let’s talk about something about CORS first. The CORS aims to restrict the access of cross-origin resources launched by script code(fetch API).

Sometimes some websites need to access the data belonging to other websites. This kind of action is dangerous. Because some malicious websites may use this opportunity to access some important data of other websites. Therefore, browsers need to limit and regulate this kind of action so developers of browsers introduce the same-origin policy into browsers. Under this policy, browsers allow a website to access another browser’s data only when these two websites have the same URI, hostname, and port number. As soon as these two websites satisfy the above conditions, these two websites are same-origin. This policy has a limitation, that the same-origin policy is only applied to the accesses launched by scripts. This means that if websites launch accesses through HTML tags these accesses will not be influenced by the same-origin policy.

Generally, because of the same-origin policy cross-site source accesses launched by scripts between different origins are forbidden. However, sometimes some websites need to access sources from different origins. To satisfy these requirements, Cross-Origin Resource Sharing(CORS) is proposed. This mechanism allows the server S to flag any origins other than itself to make browsers allow these origins’ websites to load the resource from S.

Specifically, a new HTTP header called Access-Control-Allow-Origin is added to apply this mechanism. I refer to an example from MDN to illuminate how this mechanism works.

For example, suppose web content at https://foo.example wishes to invoke content on the domain https://bar.other. Code of this sort might be used in JavaScript deployed on foo.example:

Let’s look at what the browser will send to the server in this case:

The request header of note is

Origin, which shows that the invocation is coming fromhttps://foo.example.

In response, the server returns an Access-Control-Allow-Origin header with Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *, which means that the resource can be accessed by any origin. If the resource owners at

https://bar.otherwishes that only requests fromhttps://foo.examplecan access resources, they would send headers with Access-Control-Allow-Origin:https://foo.example.

Browsers will check whether this header’s value is the same as the domain of the website that launched this access and judge whether this access is allowed. With this mechanism, when web pages request the cross-site resource the response will be denied if the responded CORS header doesn’t allow it. Some HTTP requests even need a preflight. (PUT, DELETE methods)

Reference

https://developer.mozilla.org/zh-CN/docs/Web/HTTP/CORS

https://www.chromium.org/Home/chromium-security/extension-content-script-fetches/

CORB

CORB aims to restrict the access of cross-origin resources launched by Html code.

The CORB is proposed for preventing Chrome from accessing the wrong type of documents which will cause the information leak. There are two examples below:

1

2

3

4

<img src="https://your-bank.example/balance.json" />

<!-- Note: the attacker refused to add an `alt` attribute, for extra evil points. -->

<script src="https://your-bank.example/balance.json"></script>

The first one uses the “<img>” tag to get a jSON resource while the second one uses the “<script>” tag to get a JSON resource. Because these requests are not launched by the script code, they will not be limited by the CORS and the same-origin policy. Therefore, web pages can successfully get these resources through these requests. Finally, these requested documents will enter the memory of the renderer despite the wrong file format.

It means that by using these loads which must be established for web features like <img> and <script> we can get a cross-site read opportunity. After reading this sensitive information into memory, attackers can use the side-channel attack or renderer bugs to obtain this important information. The URLs below refer to some articles about side-channel attacks which is worth studying :

[TODO]

- P0 blog: https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com/2018/01/reading-privileged-memory-with-side.html

- crbug detail: https://bugs.chromium.org/p/project-zero/issues/detail?id=1528

- some articles about spectre and meltdown:

Therefore, the CROB was introduced into the chrome. A general way to solve this problem is to check whether the format of the returned file is the same as the format asked by the page. The Browser can simply check the MIME type(from the Content-Type field of the HTTP header) of the returned file but the MIME type of an online file is not always true. Therefore, CORB will ignore the MIME type of returned files and perform a MIME sniffing to get the real type. If the format obtained by sniffing is not the same as the asked format, the content of this returned file will be emptied. This action can prevent this significant information from being read into memory which makes attackers are also can’t get that information.

Reference

https://developer.chrome.com/blog/site-isolation/

https://www.chromium.org/Home/chromium-security/corb-for-developers/

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/blocking-cross-site-documents/

Chrome Sandbox

For windows

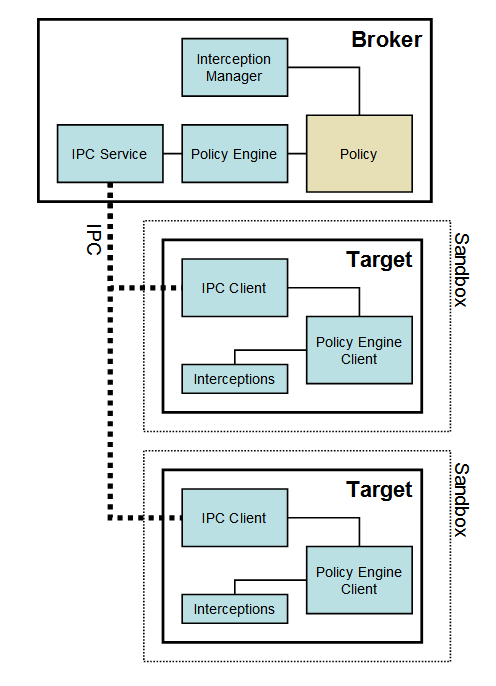

The Chrome sandbox framework for windows is formed by at least two processes: broker(server) and target(client). Broker is always the browser process and all Targets are produced and regulated by Broker. A Broker and a Target are connected by the IPC mechanism. The following picture shows the structure of the sandbox framework:

Broker process has the following functionalities:

- Specify the policy for each target process.

- Produce target processes.

- Host several sorts of service and wait for the request from Target.

- Perform the action allowed by policy on behalf of Target.

Sandbox applies a bunch of OS-provided security models such as restricted access token, job object, application container, etc., to limit Target processes to create child processes and access sensitive resources of OS such as file system and network. This means that we can not use shellcode with syscall to access significant resources such as network or file system even though we’ve got an RCE in the target process. However, sometimes target process itself needs to access some OS resources. How can Target processes access these resources? The only way is using API functions provided by the Windows system DLL.

According to the above picture, API calls from Target which are related to sensitive resources access will be intercepted by interceptions and delivered to broker process through its IPC client. Broker receive intercepted API calls from Target and then all policy-allowed API call will be invoked by broker and the results will be returned back to target. It means that API functions of Target are just wrappers and broker porcess will invoke the real API functions instead of Target.

To do these, these API functions of Target processes’ DLLs must be hooked before they are invoked and the API calls will not execute the original API functions but to execute the interception code. I’m very curious about the implementation of interception so in order to figure it out I read the source code of this part. After reading, I am aware that the interception manager of the broker process is responsible for implementing hook on these API functions.

How to Implement Interception

They define a series of customized interceptions and InteralThunks. InternalThunks is responsible for forwarding control flow to interception and it just looks like this:

1

2

01 48b8f0debc9a78563412 mov rax,123456789ABCDEF0h # this address will be replaced by the address of interception

ff e0 jmp rax

And there is an example that is NtClose()’s interception given by developer:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

// The new function should match the prototype and calling convention of the

// function to intercept except for one extra argument (the first one) that

// contains a pointer to the original function, to simplify the development

// of interceptors (for IA32). In x64, there is no extra argument to the

// interceptor, so the provided InterceptorId is used to keep a table of

// intercepted functions so that the interceptor can index that table to get

// the pointer that would have been the first argument (g_originals[id]).

typedef NTSTATUS (WINAPI *NtCloseFunction) (IN HANDLE Handle);

NTSTATUS WINAPI MyNtCose(IN NtCloseFunction OriginalClose,

IN HANDLE Handle) {

// do something

// call the original function

return OriginalClose(Handle);

}

// And in x64:

typedef NTSTATUS (WINAPI *NtCloseFunction) (IN HANDLE Handle);

NTSTATUS WINAPI MyNtCose64(IN HANDLE Handle) {

// do something

// call the original function

NtCloseFunction OriginalClose = g_originals[NT_CLOSE_ID];

return OriginalClose(Handle);

}

Let’s look at how broker process creates the target process and implements hooking on API functions of the target process’s DLL in more detail. The analysis will start from SpawnTarget() function. This function is responsible for the creation of target and all sandbox setups.

Before the implementation of interception, there will be some preparations first:

Firstly, SpawnTarget() will call the Create() function to create the new target process. When it creates a new target process, it will pass the CREATE_SUSPENDED flag to CreatProcessAsUserW() function to prevent the primary thread of the target process from being launched.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

//TargetProcess::Create() DWORD flags = CREATE_SUSPENDED | CREATE_UNICODE_ENVIRONMENT | DETACHED_PROCESS;//pass the flag if (startup_info->has_extended_startup_info()) flags |= EXTENDED_STARTUPINFO_PRESENT; bool inherit_handles = startup_info_helper->ShouldInheritHandles(); PROCESS_INFORMATION temp_process_info = {}; if (!::CreateProcessAsUserW(lockdown_token_.Get(), exe_path, cmd_line.get(), nullptr, // No security attribute. nullptr, // No thread attribute. inherit_handles, flags, nullptr, // Use the environment of the caller. nullptr, // Use current directory of the caller. startup_info->startup_info(), &temp_process_info)) { *win_error = ::GetLastError(); return SBOX_ERROR_CREATE_PROCESS; }

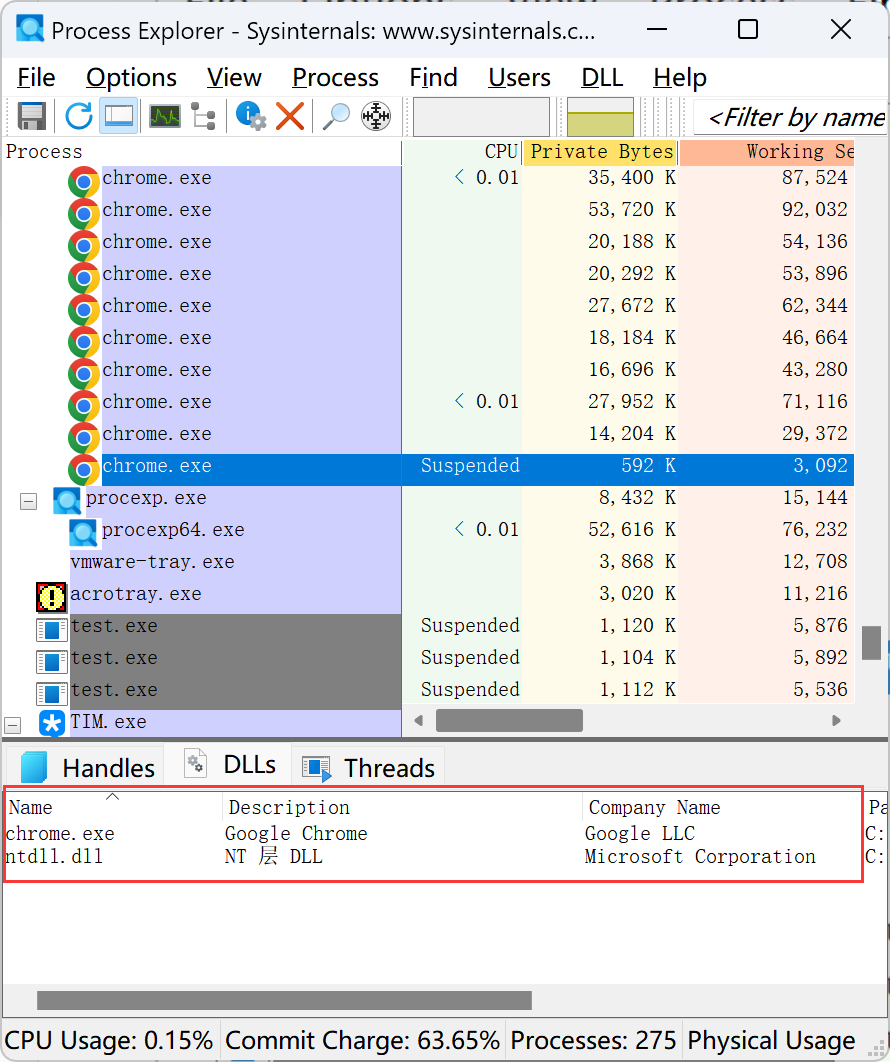

According to this article and Chapter 3 in “Windows System Internal Seventh Edition”, when we create a process with the CREATE_SUSPENDED flag, **the process which is created will stay at a stage where only the ntdll is loaded while other DLLs are not mapped into memory, and linked with Target process.** I also put a breakpoint after CreateProcessAsUserW() to observe the state of the new suspended process.

Then, after the target’s creation and the setup of the job object and low box token,

SpawnTarget()will use the following invoking chain to initialize the interception for the target process.1

SpawnTarget() -> ApplyToTarget() -> SetupAllInterceptions() -> InitializeInterceptions()

ApplyToTarget()will apply some mitigation to the suspended process first and then CallSetupAllInterceptions().The

SetAllInterceptions()function will prepare the `InterceptionData` structure for each API function that will be hooked. Each function that will be hooked will have anInterceptionDatastructure. This data structure is just like this:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

struct InterceptionData { InterceptionData(); InterceptionData(const InterceptionData& other); ~InterceptionData(); InterceptionType type; // Interception type. InterceptorId id; // Interceptor id. std::wstring dll; // Name of dll to intercept. std::string function; // Name of function to intercept. std::string interceptor; // Name of interceptor function. raw_ptr<const void> interceptor_address; // Interceptor's entry point. };

Someone may be confused about how can we get the interceptor_address of the target process in the broker process. All interceptors are the functions so we can get their addresses in the broker process directly. Moreover, one characteristic of windows ASLR is that it only randomizes the address space of a program once before the next reboot. Because the target process runs the same program as the broker process, they will have the same address space and all functions’ addresses are the same.

After gathering the information of target functions,

SetAllInterceptions()will invokeInitializeInterceptions(). This function will reorganize the interception information held byInterceptionDataaccording to which DLL it belongs to. After reorganizing, interception information of function from ntdll will be left inInterceptionDatawhile interception information from other DLL will be stored inDllPatchInfo. Each other DLL will have aDllPatchInfostructure.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

struct DllPatchInfo { size_t record_bytes; // rounded to sizeof(size_t) bytes size_t offset_to_functions; size_t num_functions; bool unload_module; wchar_t dll_name[1]; // placeholder for null terminated name // FunctionInfo function_info[] // followed by the functions to intercept }; // Structures for the shared memory that contains patching information // for the InterceptionAgent. // A single interception: struct FunctionInfo { size_t record_bytes; // rounded to sizeof(size_t) bytes InterceptionType type; InterceptorId id; const void* interceptor_address; char function[1]; // placeholder for null terminated name // char interceptor[] // followed by the interceptor function };

All these data structures will be directly used to guide the hooking process. After the preparation procedures above, the hooking process will be commenced.

There are two kinds of hook mechanism respectively for different interception.

hot interceptions: Intercept API functions from all DLLs except Ntdll. As I mentioned above, the target process is still suspended and only Ntdll is loaded into memory now. This means that the dynamic linking of other DLLs is still not performed. Therefore, we can hook the functions of these DLLs with the help of dynamic linking.

The detail is that developers use addresses of InternalThunks to patch the entries of the Export Address Table(EAT) of corresponding API functions in the corresponding DLL. Therefore, when the target process load these DLLs and perform dynamic linking, it will get the addresses of InternalThunks and put them into IAT. Finally, when we call these API functions in the sandboxed target process, InternalThunks will be invoked and result in calls of interception.

cold interceptions: Intercept API functions from Ntdll. At the moment, the ntdll has already been loaded into memory and the addresses of API functions in ntdll have been filled in the IAT of the target process and we can not just patch the EAT of ntdll to hook those API functions. Therefore, develops directly use InternalThunks to replace the bodies of API functions to hook these functions.

Let’s look at how these two kinds of interceptions in more detail.

Cold Interception

Hot interception heavily relies on cold interception so it must be set first.

InitializeInterceptions()function will call PacthNtdll(). Just like his name, this function will hook all “cold” functions for Target. However, We can not directly cover the function body of these ntdll API functions with InternalThunks because the original code of API functions still will be used in the future. We should transfer these original code to another place in the target process’s memory. Therefore, PacthNtdll() will apply for a block of memory space called remote_thunk in the target process to store the original ntdll API function code.

And then, PatchClientFunctions() will be called and PatchClientFunctions() will call the Setup() function for each InterceptionData(note: Only ntdll functions have InterceptionData now).

As we need to patch those function bodies, Setup() will call the Init() to do some check and get the address of the API function by invoking GetProcAdress(), an internal function of chromium that parses PE image to get the address of the specified export function. Moreover, If we fail to acquire the addresses of interceptors before, Init() will acquire them again.

API functions of ntdll which need to be patched are just like entries of system service. They generally have a short function body and can be divided into the following categories:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

struct ServiceEntry {

// This struct contains roughly the following code:

// 00 mov r10,rcx

// 03 mov eax,52h

// 08 syscall

// 0a ret

// 0b xchg ax,ax

// 0e xchg ax,ax

ULONG mov_r10_rcx_mov_eax; // = 4C 8B D1 B8

ULONG service_id;

USHORT syscall; // = 0F 05

BYTE ret; // = C3

BYTE pad; // = 66

USHORT xchg_ax_ax1; // = 66 90

USHORT xchg_ax_ax2; // = 66 90

};

// Service code for 64 bit Windows 8.

struct ServiceEntryW8 {

// This struct contains the following code:

// 00 48894c2408 mov [rsp+8], rcx

// 05 4889542410 mov [rsp+10], rdx

// 0a 4c89442418 mov [rsp+18], r8

// 0f 4c894c2420 mov [rsp+20], r9

// 14 4c8bd1 mov r10,rcx

// 17 b825000000 mov eax,25h

// 1c 0f05 syscall

// 1e c3 ret

// 1f 90 nop

ULONG64 mov_1; // = 48 89 4C 24 08 48 89 54

ULONG64 mov_2; // = 24 10 4C 89 44 24 18 4C

ULONG mov_3; // = 89 4C 24 20

ULONG mov_r10_rcx_mov_eax; // = 4C 8B D1 B8

ULONG service_id;

USHORT syscall; // = 0F 05

BYTE ret; // = C3

BYTE nop; // = 90

};

// Service code for 64 bit systems with int 2e fallback.

struct ServiceEntryWithInt2E {

// This struct contains roughly the following code:

// 00 4c8bd1 mov r10,rcx

// 03 b855000000 mov eax,52h

// 08 f604250803fe7f01 test byte ptr SharedUserData!308, 1

// 10 7503 jne [over syscall]

// 12 0f05 syscall

// 14 c3 ret

// 15 cd2e int 2e

// 17 c3 ret

ULONG mov_r10_rcx_mov_eax; // = 4C 8B D1 B8

ULONG service_id;

USHORT test_byte; // = F6 04

BYTE ptr; // = 25

ULONG user_shared_data_ptr;

BYTE one; // = 01

USHORT jne_over_syscall; // = 75 03

USHORT syscall; // = 0F 05

BYTE ret; // = C3

USHORT int2e; // = CD 2E

BYTE ret2; // = C3

};

After getting the address of an API function, Setup() will call IsAnyService() to judge whether the function body is consonant with one of the above code formats. If it is, Setup() will copy the original code of API function to local_thunk which is a block of memory in the broker process. If it didn’t Setup() will return an error code.

Then, Setup() will call the PerformPatch(). This function will initialize an InternalThunk for this patch. The following structure represents an InteralThunk and its interceptor_function filed has no initial value. This field will be filled with the address of the corresponding interceptor because the InternalThunk is responsible for forwarding control flow to the interceptor.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

struct InternalThunk {

// This struct contains roughly the following code:

// 01 48b8f0debc9a78563412 mov rax,123456789ABCDEF0h

// ff e0 jmp rax

//

// The code modifies rax, but that's fine for x64 ABI.

InternalThunk() {

mov_rax = kMovRax;

jmp_rax = kJmpRax;

interceptor_function = 0;

}

PerformPatch() will copy the original code of the API function from local_thunk which is in the broker process’s memory space to the remote_thunk which is in the target process memory space and has been previously requested. Then use the InternalThunk(local_service) to cover the function body. By far, the cold patch is finished.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

NTSTATUS ServiceResolverThunk::PerformPatch(void* local_thunk,

void* remote_thunk) {

// Patch the original code.

ServiceEntry local_service;

DCHECK_NT(GetInternalThunkSize() <= sizeof(local_service));

if (!SetInternalThunk(&local_service, sizeof(local_service), nullptr,

interceptor_))

return STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

// Copy the local thunk buffer to the child.

SIZE_T actual;

if (!::WriteProcessMemory(process_, remote_thunk, local_thunk,

sizeof(ServiceFullThunk), &actual))

return STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

if (sizeof(ServiceFullThunk) != actual)

return STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

// And now change the function to intercept, on the child.

if (ntdll_base_) {

// Running a unit test.

if (!::WriteProcessMemory(process_, target_, &local_service,

sizeof(local_service), &actual))

return STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

} else {

if (!WriteProtectedChildMemory(process_, target_, &local_service,

sizeof(local_service)))

return STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

}

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

}

Hot Interception

Hot interception is performed by target process instead of the broker. The broker process is only responsible for gathering the information which is needed during patching. The information is actually DllPatchInfo mentioned above. InitializeInterceptions() will call the TransferVariable() to copy all DllPatchInfo from the broker to the target process memory.

Then Broker will resume the primary thread of Target. After some initial work and before entering into the main function, the primary thread will try to load necessary DLLs into memory and these DLLs will be patched during the loading process.

To load DLLs into memory, the library loader will call an API function of Ntdll named ZwMapViewOfSection() to map a view of a section of DLLs into the virtual address space. This function has already been hooked with cold interception TargetNtMapViewOfSection(). This is also the reason why the hot patch relies on the cold patch.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

// Hooks NtMapViewOfSection to detect the load of DLLs. If hot patching is

// required for this dll, this functions patches it.

NTSTATUS WINAPI

TargetNtMapViewOfSection(NtMapViewOfSectionFunction orig_MapViewOfSection,

HANDLE section,

HANDLE process,

PVOID* base,

ULONG_PTR zero_bits,

SIZE_T commit_size,

PLARGE_INTEGER offset,

PSIZE_T view_size,

SECTION_INHERIT inherit,

ULONG allocation_type,

ULONG protect) {

NTSTATUS ret = orig_MapViewOfSection(section, process, base, zero_bits,

commit_size, offset, view_size, inherit,

allocation_type, protect);

[ ... ]

InterceptionAgent* agent = InterceptionAgent::GetInterceptionAgent();

if (agent) {

if (!agent->OnDllLoad(file_name, module_name, *base)) {

// Interception agent is demanding to un-map the module.

GetNtExports()->UnmapViewOfSection(process, *base);

*base = nullptr;

ret = STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL;

}

}

[ ... ]

return ret;

}

After calling the original ZwMapViewOfSection() to map the DLL into memory, TargetNtMapViewOfSection() will call OnDllLoad() to patch all functions which are needed to be hooked in this DLL and here is a description of OnDllLoad() from developers.

This method should be invoked whenever a new dll is loaded to perform the required patches. If the return value is false, this dll should not be allowed to load.

This function will patch EAT of Target’s DLLs. Therefore, we need addresses of EAT entries of API functions instead of addresses of the function itself. Then, the following procedures are the same as cold patch. It will prepare an InternalThunk for this patch. After calculating the RVA of InternalThunk, RVA will be written to that EAT entry. These are all done in Setup.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

NTSTATUS EatResolverThunk::Setup(const void* target_module,

const void* interceptor_module,

const char* target_name,

const char* interceptor_name,

const void* interceptor_entry_point,

void* thunk_storage,

size_t storage_bytes,

size_t* storage_used) {

NTSTATUS ret =

Init(target_module, interceptor_module, target_name, interceptor_name,

interceptor_entry_point, thunk_storage, storage_bytes);//get address of EAT entry

if (!NT_SUCCESS(ret))

return ret;

if (!eat_entry_)

return NTSTATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER;

#if defined(_WIN64)

// We have two thunks, in order: the return path and the forward path.

if (!SetInternalThunk(thunk_storage, storage_bytes, nullptr, target_))

return STATUS_BUFFER_TOO_SMALL;

size_t thunk_bytes = GetInternalThunkSize();

storage_bytes -= thunk_bytes;

thunk_storage = reinterpret_cast<char*>(thunk_storage) + thunk_bytes;

#endif

if (!SetInternalThunk(thunk_storage, storage_bytes, target_, interceptor_))

return STATUS_BUFFER_TOO_SMALL;

AutoProtectMemory memory;

ret = memory.ChangeProtection(eat_entry_, sizeof(DWORD), PAGE_READWRITE);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(ret))

return ret;

// Perform the patch.

*eat_entry_ = static_cast<DWORD>(reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(thunk_storage)) -

static_cast<DWORD>(reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(target_module));

if (storage_used)

*storage_used = GetThunkSize();

return ret;

}

After all these works, all interceptions are prepared and Target processes can access system resources through these interceptions.

An interception will invoke the origin API call first to check whether this API function can still work. If the invocation of origin one is not denied by the system, the interception will just return. Otherwise, the interception will use IPCs to forward this invocation to the broker process. In the broker process, some API functions are controlled by policies. All the API calls which are allowed by policy will be invoked by Broker and the result will be returned to Target.(TODO: The source code of how to deal with policy is too complicated and I have not read it.)

For linux

Just like the sandbox framework on windows, Linux sandbox is also formed by a Broker process(browser process) and a Target process and it has two layers.

- Layer-1 (also called the “semantics” layer) prevents access to most resources from a process where it’s engaged. This layer is based on the namespace mechanism of Linux.

- Layer-2 (also called the “attack surface reduction” layer) restricts access from a process to the attack surface of the kernel. Seccomp-bpf is used for this.

Because different Target processes will have different sandbox configurations, I will only focus on the sandbox of the renderer process on the Linux platform in this section.

Zygote

Before introducing the Layer-1 sandbox for linux platform, we need to know how a Broker process spawn Target processes on linux.

On the Windows platform, a broker process will just call the CreateProcessAsUserW() to launch a new Chrome process with specific arguments as the target process which may be a renderer process or a GPU process, etc. While the process launch model of Linux is different from windows. A Linux parent process doesn’t launch a new process directly. It invokes fork() to copy itself first and then calls execute() to load the target binary file. This unique launching model of Linux provide developers an opportunity to optimize the launch process of Target.

We all know that the launch of process has lots of overhead:

- The kernel needs to fork the parent process first.

- And then it will load the target file and perform the dynamic linking.

- Moreover, after entering the main function, a process with complicated functionality needs to do lots of initial setups such as sandbox setup before its working logic.

In order to reduce this overhead, developers brainstorm a method to skip all these procedures:

Before launching a target B, broker will launch(fork + execute) a target process A first.(LaunchProcess())

The A will finish all these procedures (dynamic linking, initial setups(include Layer-1 sandbox)). Then A will stop and wait for signals from Broker with function

ProcessRequests(). (ZygoteMain())The broker process will send a signal and necessary arguments to tell A that it needs a new target process B that which be a renderer process or GPU process.

The A will fork itself as B and update arguments for B. Then, B will work as the broker process expects.

![image-20230103172257502]()

The process A is just like a fork-server which is used in AFL to accelerate the launch of the tested program, while in Chromium process A is called zygote. Besides accelerating the launch process, this mechanism is also be used to make Chromium adapt to the update model of Linux according to this article.

Because the target processes are forked from the zygote and the namespace of processes can be inherited, the Layer-1 sandbox of the target process is based on the that of the zygote.

Layer-1

This article has a detailed introduction to namespace.

Layer-1 of the target process is mainly formed by pid_namespace, user_namespace, network_namespace, and chroot jail while user_namespace, network_namespace, and chroot jail are inherited from the zygote and a the target process only has its own pid_namespace. So what are these namespaces’ functionalities?

- pid_namespace: individual pid_namespacce prevent a Target process from accessing other processes outside the pid_namespace. In this way, Target process can’t debug other processes or dump other processes’ memory.

- user_namespace: Use unprivileged user_namespaces to limit a Target process’ capabilities.

- network_namespace: Prevent a Target process from accessing network resources.

- chroot jail: Prevent Target process from accesssing file system of user.

Let’s look at how these things are implemented in more detail.

Implementation Detail

Zygote will enter Layer-1 first and its logics are in EnterLayerOneSandbox().

Firstly, a zygote will be launched.

In this step, Broker will use Clone() to launch a zygote with CLONE_NEWUSER, CLONE_NEWPID, and CLONE_NEWNET flags. Therefore when this zygote is launched, it will have its own user_namespace and pid_namespace and network_namespace.

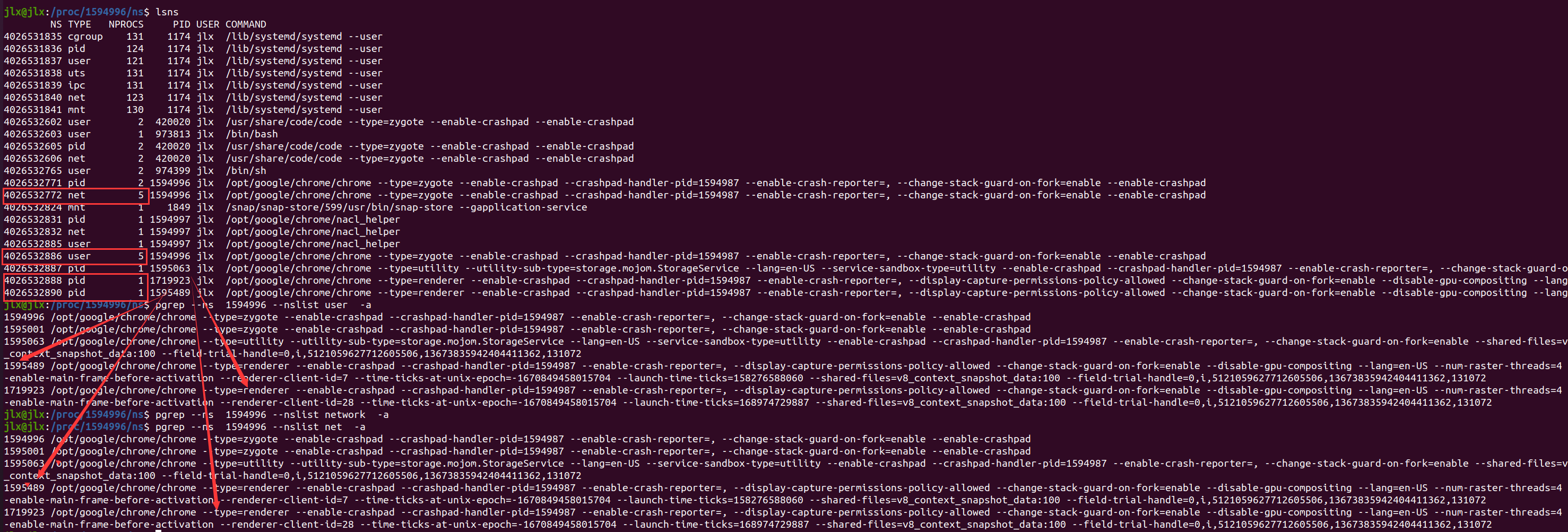

Then, the zygote will fork itself. The parent will be the init process of the new pid_namespace and the child will continue to work and be responsible for forking other target processes. If the parent dies all the processes in this pid_namespace will die. As we can see in this picture.

![image-20221220113650830]()

- Secondly,

DropFileSystemAccess()will be invoked and this function will continue to invokeChrootToSafeEmptyDir()to create a chroot jail for this zygote. It will clone a new process C and chroot zygote’s root directory to the/proc/pid/fdinfo/of C and then C will exit and the zygote will lose its access ability to the file system. - Thirdly, the zygote will drop capabilities gained by entering the new user namespace with

DropAllCapabilities(). After this step, the zygote will completely enter Layer-1.

Then zygote will wait for the instructions from Broker. As soon as the zygote accepts a forking request from Broker, it will fork itself and the child process will be a new target process. Meanwhile, the child will also inherit all zygote’s sandbox setup. All this setup will be remained except that the child will create its own pid_namespace in order to prevent it from accessing other processes in the zygote’s pid_namespace.

As we can see from the above picture, two renderer processes ohave its own pid_namesapce and they share a network_namespace and user_namespace with the zygote.

In this way, the Target process enters its own Layer-1 sandbox.

Layer-2

The Layer-2 sandbox of the Target process is mainly about seccomp-bpf which is a security feature provided by the Linux kernel. And its main responsibility is to filter syscalls and reject dangerous syscalls. For more details about seccomp-bpf, I recommend two materials:

- “The BSD Packet Filter: A New Architecture for User-level Packet Capture”: This paper includes a detailed introduction to BPF.

- “Linux Observability with BPF”: This book mainly talks about the usage of BPF and its Chapter 8 tells us how to use the seccomp-bpf.

Layer-2 sandbox designs a specific filtering policy for each kind of process. :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

ResultExpr RendererProcessPolicy::EvaluateSyscall(int sysno) const {

switch (sysno) {

// The baseline policy allows __NR_clock_gettime. Allow

// clock_getres() for V8. crbug.com/329053.

case __NR_clock_getres:

#if defined(__i386__) || defined(__arm__) || \

(defined(ARCH_CPU_MIPS_FAMILY) && defined(ARCH_CPU_32_BITS))

case __NR_clock_getres_time64:

#endif

return RestrictClockID();

case __NR_ioctl:

return RestrictIoctl();

[...]

default:

// Default on the content baseline policy.

return BPFBasePolicy::EvaluateSyscall(sysno);

}

}

The above code is the policy of the renderer process which is derived from the baseline policy(Actually, all kinds of policies are derived from the baseline policy.). It will use the sysno and the arguments of a syscall to judge whether to allow this syscall to execute normally. And there will be three cases:

- This syscall is allowed by the policy.

- This syscall is denied by the policy.

- The policy will emit a SIGSYS signal to trigger a trap. By registering trap handling processes, it allows user-land to perform actions such as “log and return errno” or forward this syscall to its specialized broker process to perform a remote syscall via IPCs.

Then, the C++ filtering policy will be translated into bpf code by AssembleFilter(). This bpf code will be sent to the Linux kernel and there will be a VM in the kernel which is responsible for interpreting the bpf code and filtering all syscalls invoked by this target process. The Layer-2 sandbox is designed to reduce the possibility of the kernel being attacked by the code executed in userland. For example, if some attackers get the ability of executing arbitrary shellcode in the renderer by exploiting some vulnerabilities in it, the Layer-2 sandbox can effectively prevent attackers from invoking syscalls to damage the kernel.

Access to System Resources

With these two kinds of sandbox, the target process will be isolated strictly and can hardly access system resources. However, sometimes, a target process indeed needs to access some sensitive system resources which are outside the sandbox on Linux. For example, sometimes, a target process may need to open a file but open() syscall is forbidden according to the baseline bpf policies.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

ResultExpr EvaluateSyscallImpl(int fs_denied_errno,

pid_t current_pid,

int sysno) {

[ ... ]

if (SyscallSets::IsFileSystem(sysno) ||

SyscallSets::IsCurrentDirectory(sysno)) {

return Error(fs_denied_errno);

}

[ ... ]

}

As I mentioned above, on Windows, developers hook the system API functions to forward all syscalls to the browser process. However, on Linux, they use a different method.

Because the source code of Chromium is too complex for me to figure out how it implements the access of system resources. Therefore, I asked this question on the Google Group of Chromium security and got replies(very patient replies). According to it, we can conclude that developers design two kinds of access mechanisms:

- For the renderer process which basically doesn’t use third-party code, developers explicitly replace syscalls with mojo operation and forward

open()syscall requests to the browser process. - For some other target processes such as the GPU process and the utility process, because they use too much third-party code like STL, it is hard even impossible for developers explicitly modify all this code. Therefore, they use the following steps to deal with this problem:

- Firstly, each process will have its own “broker process”(This broker process which is forked by target process is not the browser process.)

- Secondly, they cover the baseline bpf policies for these processes. The new policies will trigger a trap for an

open()syscall and then the corresponding trap handler which is registered previously will be invoked to rewrite this syscall into IPCs over to its broker process.

By using these two methods, developers make sure that normal access to system resources can be fulfilled and browser processes can execute normally in the sandbox.

Developers use traps and trap handlers instead of hooks just like on Windows. This may be because there are too many third-party functions on Linux using syscalls directly. However, on Windows, high-level third-party functions always invoke API functions in Ntdll to access syscalls. Therefore, for example on windows, we can only patch functions in Ntdll while on Linux, we need to patch functions like printf() instead of write(). It will need developers to spend lots of time to maintain.

Reference

https://patricia.no/2019/01/25/linux_security_in_the_chromium_sandbox.html